Tag: Inspiration

Wisdom for Teams #12

—

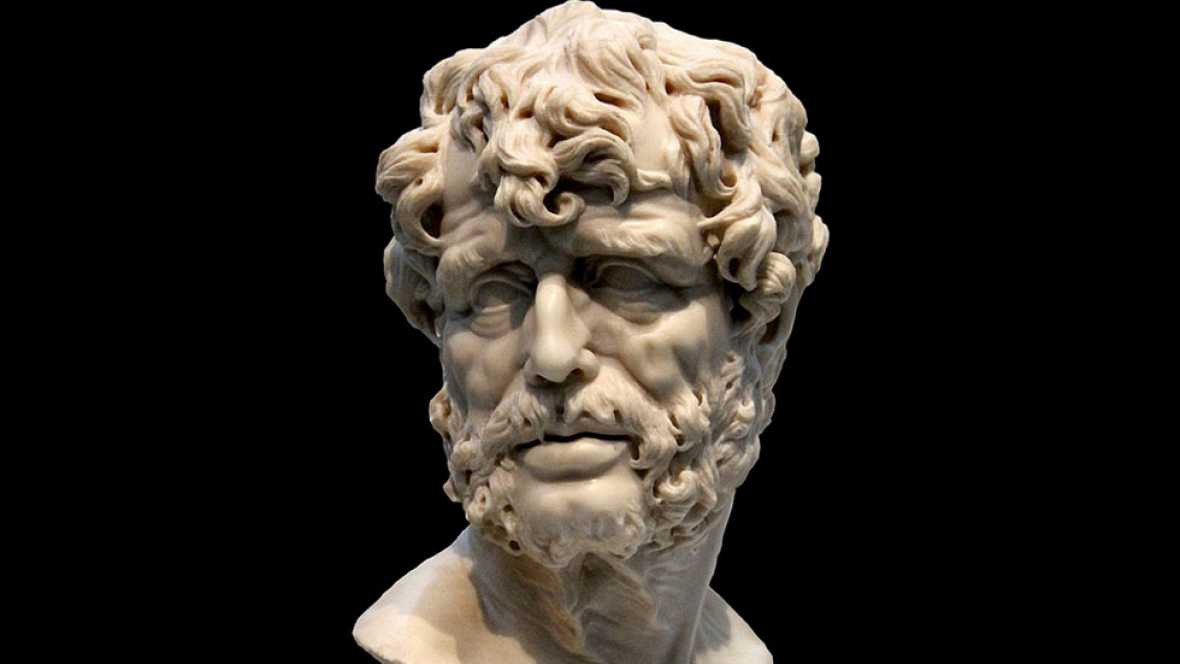

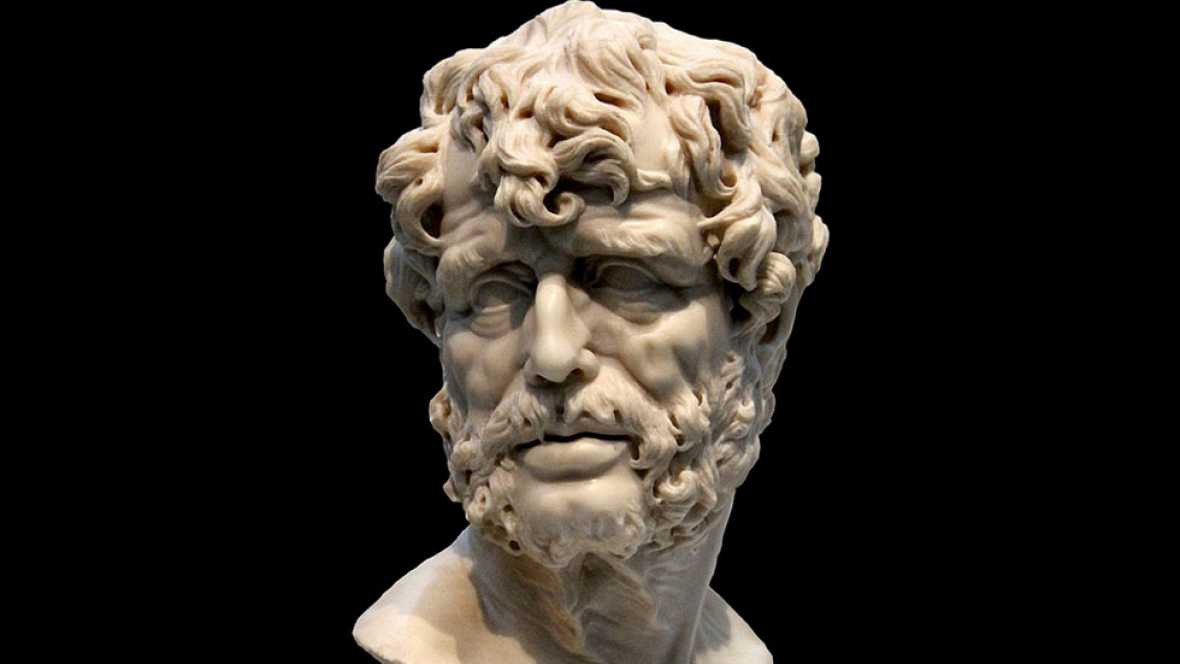

“You must lay aside the burdens of the mind; until you do this, no place will satisfy you.”

—

SENECA (c. 4 BC – AD 65), Roman Stoic philosopher, statesman, and dramatist

Wisdom for Teams #11

—

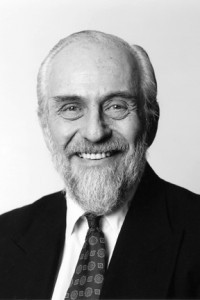

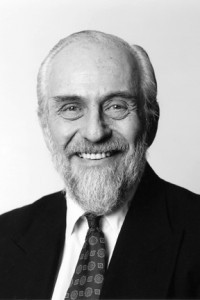

“I’ve always been the opposite of a paranoid. I operate as if everyone is part of a plot to enhance my well-being.”

—

STAN DALE (1929-2007), radio broadcaster, writer, teacher, and founder of the Human Awareness Institute.

My Wish For You

—

Yesterday on a news panel on how to celebrate Christmas, one of the commentators asked: Celebrate what? He then proceeded to argue there is nothing to celebrate this year. It’s been a shitty year, and Christmas is miles away from what it would typically be, but…

—

Do you really have nothing to be thankful for?

Is there nothing in your life worth raising a glass?

—

My past few Christmases haven be awful. Last year was cool because we were in Mexico with family. But the previous year, six days before Christmas I broke my collarbone, and the one before that I had a terrible, terrible argument on Christmas Eve.

I had little or no say in these events. But this year, I have a choice because we have all known for months that things would be different. I get to choose what to focus on:

—

Will I count my blessings or my problems?

—

This is not about my subjective opinion in seeing the glass half full in my life. Instead it is about objectively noticing that I have a glass to begin with. Christmas this year will be spent with my daughter, Irene, and with luck, a few true friends. This is blessing enough for me — other than the fact that there will be plenty of red wine and, hopefully, sense of humor.

My wish for you is that you may be inspired to notice some of the blessings in your life, so as to savor Christmas Day with a profound sense of meaning. Merry Christmas!

The POOH System to Get Creative

—

How do people who have great ideas come up with them? Do those who rely on inspiration to do their work use a special system? What strategies do marketeers, writers, artists, designers, and more, use to create new work?

I recently read a book on this topic as preparation for an offsite I was asked to create. In Strategic Intuition, William Duggan reviews some of History’s most creative minds to distill the formula they used to come up with innovative solutions.

I’m not going to share the formula (at least not all of it) because the book is really worth the read. Instead I’ll share how it relates to the creative work I do. I design and deliver offsites for executive teams, often the same teams. So coming up with different ideas for the same crowd can be a challenge.

The team leader who suggested I read book, whom I’ve been working with for years, said: “If you look at how you prepare your offsites, you’ll probably notice that the elements of the formula are somehow involved in your creative process.”

Now that’s an interesting endeavour. So I did and I noticed that in fact there is a pattern — hence the acronym “POOH” — that I have been using for nine years to build workshops and facilitation sessions. I believe it can be applied for other creative purposes. So here it goes for you to try the next time you need ideas.

After meeting with the team lead, and bearing in mind that the mind cannot not answer a question, I consider the following:

Purpose: I ask myself: Why are we going to do this? What meaningful reasons do we have? I answer this in one short sentence. Nietzsche said that those who have a why to live for can bear almost any how. Purpose is powerful. Purpose is the engine of creativity, while also being the guard rails of the creative process. No guard rails on the road means you can end up derailed. An example of a purpose for a team offsite is: We’re doing this because we rely on trust to get work done, and we want to increase trust in the team.

Objectives: I ask myself: What needs to be done? What needs to happen? I write down all that comes to mind. Then, even if I have no idea yet of how to achieve this, I choose the top three specific actions I’m aiming to achieve. Given the purpose above, an example of an objective could be: Show vulnerability to teammates.

Outcomes: I ask myself: What will be the consequences of achieving these objectives? Here we are looking for the end state that emerges from achieving the specific actions. Outcomes allow us to assess to the degree to which we’ve achieved the objetives. Given the above, an example of an outcome is: Teammates express a renewed appreciation for one another other, as a consequence of everyone having shown vulnerability.

Hunches: I ask myself: If I knew how to make all this happen, what would I do? I write down whatever comes to mind. These are the intuitions of how we’ll achieve the objectives, the gut feeling about the strategies that will lead to the outcomes. An example of a hunch in this case is: Share a personal story about a failure in life.

And that’s it. Like all good wine, ideas need to age. I’m done for now. I’ve given my mind all the information it needs in order to search my memory files and combine information is a new way to come up with new ideas. And my mind does.

In the course of the following week, or two, ideas pop up. And when they do, I write them down in the same place. Lo and behold I now have enough material to design a new, relevant and coherent offsite.

What is your process for creative work? Do we have anything in common? Is this useful in any way? I would love to hear from you.

BTW, the “search” and “combine” bits are part of the formula in the book. 😉

PS: Special thanks to my friend Marie Eouzan for inspiring the idea for this post. 🙂

A Story About Assumptions, Surprises, and More

Photo courtesy of One Day Web Group

—

In the year 2004-2005, I worked as a hospital chaplain, the priest that visits patients at the hospital. It was a year of great learning. This story is conceivably my greatest lesson learnt.

—

—

This was recorded as part of a storytelling evening organised by Lukas Liebich. You can learn more about it here: https://www.facebook.com/events/59426…

Be. A message for leaders in confinement.

13 public speakers, members of keynoteboutique.com, join rhetorical forces to bring you a comforting message in these challenging times.

—–

—

Music by Alexander Nakarada | https://www.serpentsoundstudios.com

The Trust Story

This meant he didn’t really trust anyone.

Except for one person: his special friend. It took him more than 10 years to do so. Before trusting him, he assessed the events that indicated his special friend was worthy of trust:

– When I wanted to go for a drink, my friend was always ready.

– When I renovated my apartment, my friend booked all his weekends until it was done.

– Even when I considered a career change, my friend was there to carefully listen and give good advice.

– And when my mom died, my friend never once left my side.

For the first time the man felt he was ready to trust.

The next day, his special friend died.

For the remainder of his days, the man wondered if his friend had also trusted him. And when they met in the afterlife, the first thing the man did was ask his friend if he had been trustworthy, and if so, when had he decided to trust him.

Staring at the man with a look of confusion on his face, the special friend said:

Of course you’re my trusted friend! I decided to trust you the day we met. And ever since you’ve never betrayed my trust:

– Whenever you needed a favor, you trusted me to ask for help.

– When you wanted to go for a drink, it was me who you choose to confide your secrets.

– When you renovated your apartment, you allowed me and no other to enter the privacy of your home to rebuild it.

– Even that time — remember? — when you were considering a career change, again it was me who you turned to for advice.

– And when your mom passed, I was the only one you accepted at your side.

Your actions have taught me the meaning of trust!

The man stood there in shock, thinking:

You never fully know what people are capable of. By this token, you’ll never really know when you can trust someone.

Credits: I first heard of a credit for trust from my dear friend Florian Mueck.

Two Signs Of Good Advice

The other day my friend and colleague, Sebastián Lora, visited Barcelona and we met for a stimulating Gin&Tonic. He asked for my opinion about a workshop he’s preparing for Toastmasters. I gave one at last year’s District Conference, so I shared my experience.

Afterward, I wondered if I’d given useful advice. I began to reflect on criteria to recognize good advice. Family, friends, colleagues and professors whose counsel I deeply value came to mind. What do they have in common? Two things stood out:

Questions instead of recommendations

are a sign of good advice.

1. The people who give me good advice never say: “you should do this”. They have in common that they ask questions that help me discover what to do. This is a sign of wisdom.

They know no two situations are the same, that their experience is always their experience. And if they have a pretty good idea about what to do, even so they use questions to help me see the way, not just the finish line.

Tell me how – now that’s priceless!

2. Good advice consists of “how” not “what”. The people who’ve helped me improve and grow are those who’ve suggested specific alternatives.

General advice is easy to get — and give! — because it requires no real effort: do this, do that, be this, be that, blah, blah, blah! But find someone who tells you HOW you can do it, who suggests SPECIFIC ways and you’ve found a true treasure!

The world is full of people with a message.

There are few with a method.

You know you’ve found a good adviser when you hear questions that help you decide rather than recommendations that tell you what to do.

You know you’ve found a good adviser when you hear specific suggestions to improve instead of general guidelines to follow.

Did I live up to these criteria with the advice I gave to Sebastián? Only he can say. 🙂 I do remember asking questions and giving a few tips. But there’s no doubt: next time I’ll do better following these two principles!

How do you recognize good advice?

Grandpa Jose’s Effectiveness Recipe

My grandfather was born in the Azores Islands in 1906. His schooling literally lasted two days: the first and the day after. He got punished, didn’t like it, left and never went back.

Grandpa didn’t learn to read or write. Grandpa didn’t really know who Aristotle, Shakespeare or Karl Marx were. Grandpa didn’t rely on business trainings or performance enhancement models. Grandpa was a farmer.

One day, when he was but a young man, his dad gave him and his brother a gift: a pregnant young cow for the two to start their lives as herdsmen. Two years later, his brother owned two head of cattle; grandpa Jose, seven. From then on, his success kept multiplying, considerably.

This afforded him the opportunity to savor life, especially his passion for discovering the wonders of the world. In the end, grandpa grew to be quite the philosopher, readily armed with the precious pearls of common sense and practical wisdom.

The recipe of his effectiveness? He used say he remembered that often at the end of the day while he sat by the sunset reflecting, he’d notice his brother in the distance, still tilling the earth, persistently putting his back into every strike.

“Before the sun rose,” he used to say, “John would already be out on the field. And not before dark would he return! — All hard work and diligence. I did it differently. Every morning I’d ask myself: ‘What do I have planned for the day?’” Then he’d think:

How can I accomplish twice as much with half the effort?

Grandpa kept at it until he found an answer. Most of them eventually worked.

I gather an important lesson from my grandfather: To make it an undying habit to stop, rethink and improve. I’m sure he would be happy to know that Aristotle thought along similar lines: “We are what we repeatedly do. Excellence, therefore, is not an act but a habit.”

I must confess, though, I sometimes recognize a bit of great-uncle John in me. What about you: with whom do you most identify with?

Rage Against The Dying Of The Light

In this poem “Do Not Go Gentle Into That Good Night”, Welsh poet and writer, Dylan Thomas proclaims that the wise and good do not go gently into the good night of death.

Instead, they rage against the dying of the light, against the demise of what wisdom and good their words and deeds may have effected in the world.

Though good and wise leaders must die, as we all,

their light need not follow them into the good night.